Continuous Integration, Continuous Delivery, and Continuous Deployment are key modern practices in software development. These techniques help us reduce integration problems, automate quality assessment and make deployments much more predictable and less error prone, allowing us to deploy easily and frequently. But… Do you really know the differences between the three?

The aim of this article is to help clarify what do these techniques mean and highlight the benefits each one provides. We will also analyze which one should be chosen depending on the circumstances.

This year I have been deeply involved in the subject, since I have been working on setting up Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery in Platino, which is a big government project that has been around for almost 10 years. Platino receives tens of millions of requests every month and has a considerable codebase, being composed of more than 50 web services and 9 web applications.

During this time I have realized that, despite the importance of these practices, many professionals in the industry still miss the differences between the three, often talking about them indistinctly in conversations, which creates a lot of confusion around the topic. So, let’s check the differences:

Continuous Integration

The concept of Continuous Integration (CI) was originally proposed by Grady Booch in 1991 and later integrated into Extreme Programming. From then on, specially thanks to the Agile Software Development movement (as well as DevOps culture), the technique has been widely adopted in the industry.

Core proposition

The core proposition of Continuous Integration is associated with Version Control Systems (VCS). It was originally described as a simple technique, which consisted of integrating developers’ work (their working copies or branches) to the mainline (trunk in subversion or master branch in git) at least once a day.

The idea behind these daily integrations to the mainline is to reduce integration problems, which are usually caused by the complexity of merging the work of developers that have been working isolatedly for a while. By integrating daily or after each commit, the complexity of the merge process is drastically reduced, as can be seen in the following example:

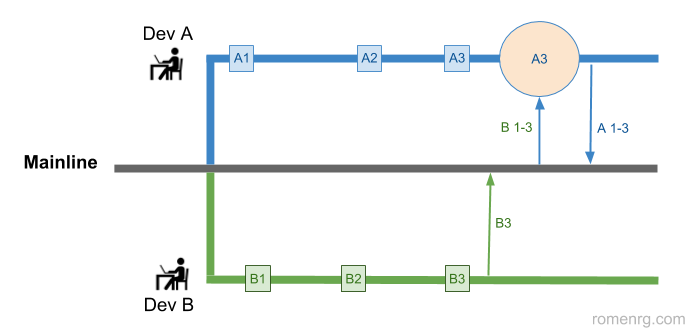

Example of two developers creating several commits in their corresponding branches before merging. Squares represent commits and the circle represents the big merge that has to be made at the end.

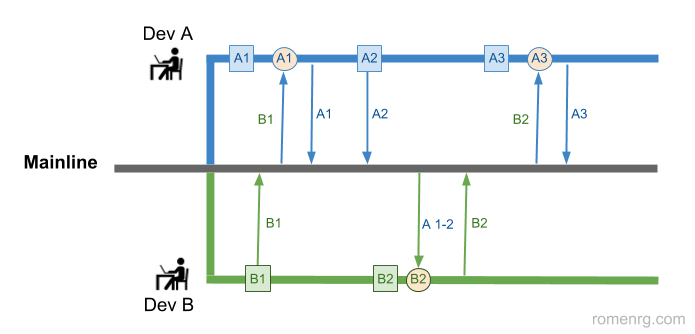

Example of two developers applying the original concept of Continuous Integration, integrating every change into the mainline. As before, squares represent commits and circles represent merges, which are much simpler now, due to the high frequency of integration.

Extended Continuous Integration

Although the core proposition of CI, described above, has value on itself, the definition of Continuous Integration was soon broadened. Nowadays, it often implies the existence of a CI Server (such as Jenkins) that, once a new change is made to the mainline of the VCS, executes a Continuous Integration Pipeline. These pipelines are formed of different stages, executed sequentially on every integraton. Their goal, as Martin Fowler states, is to verify every integration with an automated build, to detect integration errors as quickly as possible. These builds include at least the compilation of the source code and the execution of unit tests, although in many cases other stages such as packaging, execution of integration / end-to-end tests and static code analysis are also included in these Continuous Integration Pipelines.

In this extended definition, the pipeline can either finish successfully or a failure can be produced in any of the stages (tests failing, static analysis not passing a defined threshold….). Usually, in the event of a failure, a notification email is sent to the person that created the last commit (probably the one causing the failure). In such cases, in order to really get the benefits of Continuous Integration, it should be a priority for the team to keep the Continuous Integration status green (passing) instead of red (failing), fixing any problem as soon as it is detected (ideally in less than 10 minutes).

Following this approach, automated builds with several checks are performed to our code every time we integrate changes, allowing us to detect any issues in an early stage. This quick detection of problems makes fixing them much cheaper than in traditional approaches. When these automated builds are not in place, detection of problems tends to occur much later, often during QA or deployment phases, and many times in production, after having deployed the new version. In those cases, days, weeks or even months have passed and developers have switched context, making it difficult for them to remember the particular cases they were working on when the problem was produced. Moreover, the higher pressure for deployment deadlines at those later stages usually leads to poorer solutions, that not only hinder code quality (reducing its readability and mantainability) but also tend to introduce new bugs.

Continuous Delivery vs Continuous Deployment

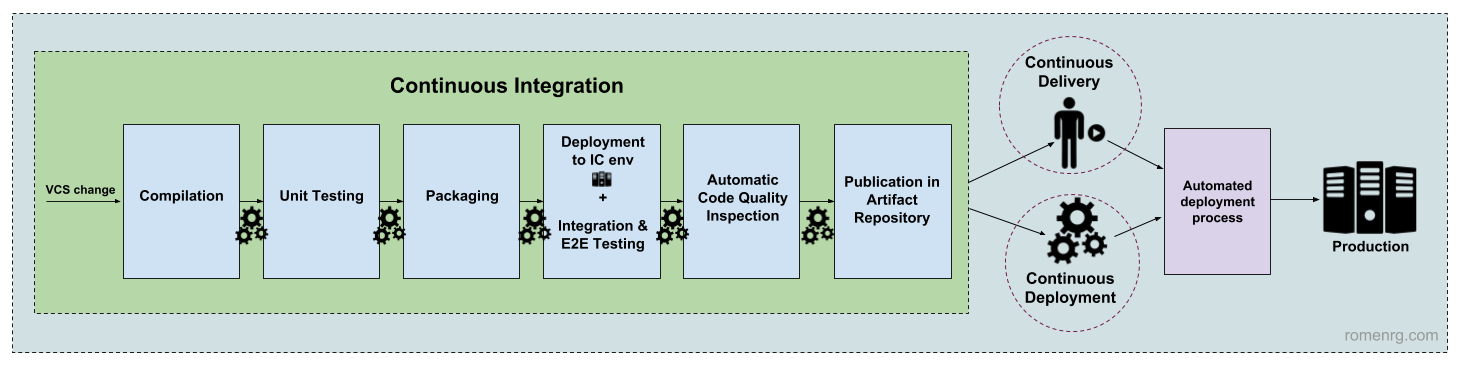

Once Continuous Integration is set, we may decide to continue improving our processes. The next step would be automating deployments to production, making them faster and safer. Here is where the two remaining techniques (Continuous Delivery and Continuous Deployment) subtly differ, as can be see in the following diagram:

Difference between Continuous Delivery and Continuous Deployment

Differences explained

Continuous Delivery was described by Jez Humble, as “the ability to get changes of all types […] into production, or into the hands of users, safely and quickly in a sustainable way”. Continuous Delivery does not necessarily involve deployment to production on every change. We just need to ensure that our code is always in a deployable state, so we can deploy it easily whenever we want. On the other hand, Continuous Deployment requires every change to be always deployed automatically, without human intervention.

Thus, as can be seen in the image above, if we decide to enhance the pipeline so that, once the Continuous Integration stages are completed, the new artifact is automatically deployed to production, we talk about Continuous Deployment. On the other hand, if we manage to automate everything, but decide to require a human approval in order to proceed with the deployment of the new version, we are talking about Continuous Delivery. The difference is subtle, but it has huge implications, making each technique appropriate for different situations, as we will see below.

If you need some other references, appart from this article, to be convinced about this difference, notice that a few years ago Puppet published a similar comparison in their blog. Also, Atlassian has published a longer article on the topic. I hope these articles help clarify these concepts, avoiding the current confusion with them.

When is Continuous Deployment recommended and when should we opt for Continuous Delivery?

In general, Continuous Deployment is great for B2C products, since as consumers we are used to the constant change of software products, usually assuming their changes without major problems. In fact, consumer companies such as Facebook or Netflix follow this approach, deploying small changes several times a day to production.

However, in B2B products as well as in government projects, it is often necessary to include human control to activate deployments to production. In these cases, our changes may affect people and processes in other companies or departments, making it important for us to announce release dates with enough time, so everybody is able to update their processes, learn to use the new features we are about to release or even adapt their software to our API changes. In this context, applying Continuous Deployment (deploying automatically every change to production) could make other software crash, prevent people from doing their job or even lead to economic and legal issues. That is why for these cases, in which we have to set a fixed deploy date, Continuous Delivery is the technique of choice, as is our case in Platino. Following this approach we can also automate the whole process, but we provide human control to execute deployments to production, thus controlling when the new version is released.

Go ahead!

As mentioned above, these processes are key elements in modern-day software development and provide a significant competitive advantage to software companies applying them. As we have seen above, depending on the software being developed and its usage, we may not be able to opt for Continuous Deployment, being Continuous Delivery the alternative of choice. However, Continuous Integration is the essential practice that serves as a basis for the other two, making it the preferred choice to start off with.

Significant revisions

2018, Jun 24: Figure ‘continuous delivery vs continuous deployment’ improved.

2018, May 28: Overall style improvements, rephrasing last section, adding a better description and improving example images.